“Well, it certainly was powerful…”

“I didn’t understand much…”

“I don’t know, maybe I just don’t belong to this genre…”

“Technical level certainly original…”

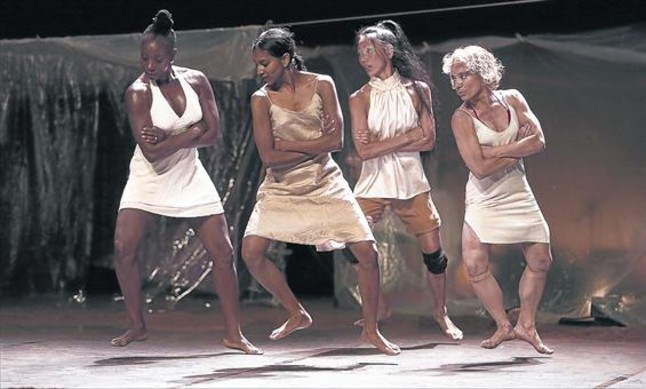

These were the comments that accompanied people (especially women of various ages) standing outside the Auditorium of Roma, after WeWomen was staged during the Dance Festival “Equilibrio” in 2016, a contemporary dance show conceived, played, sung and performed entirely by women. According to the director’s website, the show is still on stage around Europe.

So I asked myself: beyond originality, technique and power, is it possible to define a work of art successful, if, in the end, it is not understood? (especially from those directly interested…)

From the synopsis the intentions of the show seemed clear and enormous: the director, the Spanish and blonde Sol Picò, puts into play her point of view on the “condition of women” today, dancing together with the Beninese Julie Dossavi, the Japanese Minako Seki and the Indian Shantala Shivalingappa. All different women, from Africa, Asia and Europe, who together, each with her physicality and particular dance style, show what they have in common: an often depressing life condition.

How simple bodies could interpret all this seemed yet difficult. In fact, there is not only dance: there is live music (Sevillian guitar by Marta Robles and crazy violin, almost speaking, by Adele Madau, which looks Spanish, but she is Sardinian), singing (a splendid voice in a truly poignant flamenco by Lina Leòn), some dialogue or monologue (often incomprehensible due to the busted language or subtitles), and an earthy scenography, from a refugee camp. A disturbing barking of dogs all around.

Certainly the life of a woman can be depressed in various ways, more or less large or serious: without immediately touching the bottom of physical violence or stoning, there is perhaps depilation (which is almost an anagram!) And the “bikini-test”, for example, that contribute to reducing women to bodies, obsessed by few functions: pleasure, loyalty, motherhood, kindness, perfection… There is the fact that women often serve men, and then maybe they eat alone and last, consuming their scraps. Quite normal in certain countries, because this is what the “natural generosity” imposes on women. At least Shantala (the dancers are called by name) seems to be convinced of this.

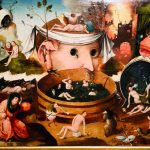

Certainly there are many feminine symbologies: the generating Earth, precisely, in which they roll and crawl, or the apples (of sin), which fall on them and maybe in their mouths, letting women unable to sing anymore, as if they were stuffed pigs. There are stereotypes: hanging clothes, folded ones, brooms, fitness nudity. The Sardinian who talks about cooking. Then there are other lesser known, observed or exalted realities: muscular power or women against women, because they are always the ones who throw stones at the shadow of a veiled woman. Just a shadow, indeed.

Everything is put against each other, together, on a single stage. The effect is that the stereotype actually disappears.

We usually think that women are beautiful, clean, graceful (so are the dancers) and sexy. Here are some dirty women, sometimes aggressive, with naked bodies that do not transmit sex, but something else far more animalistic.

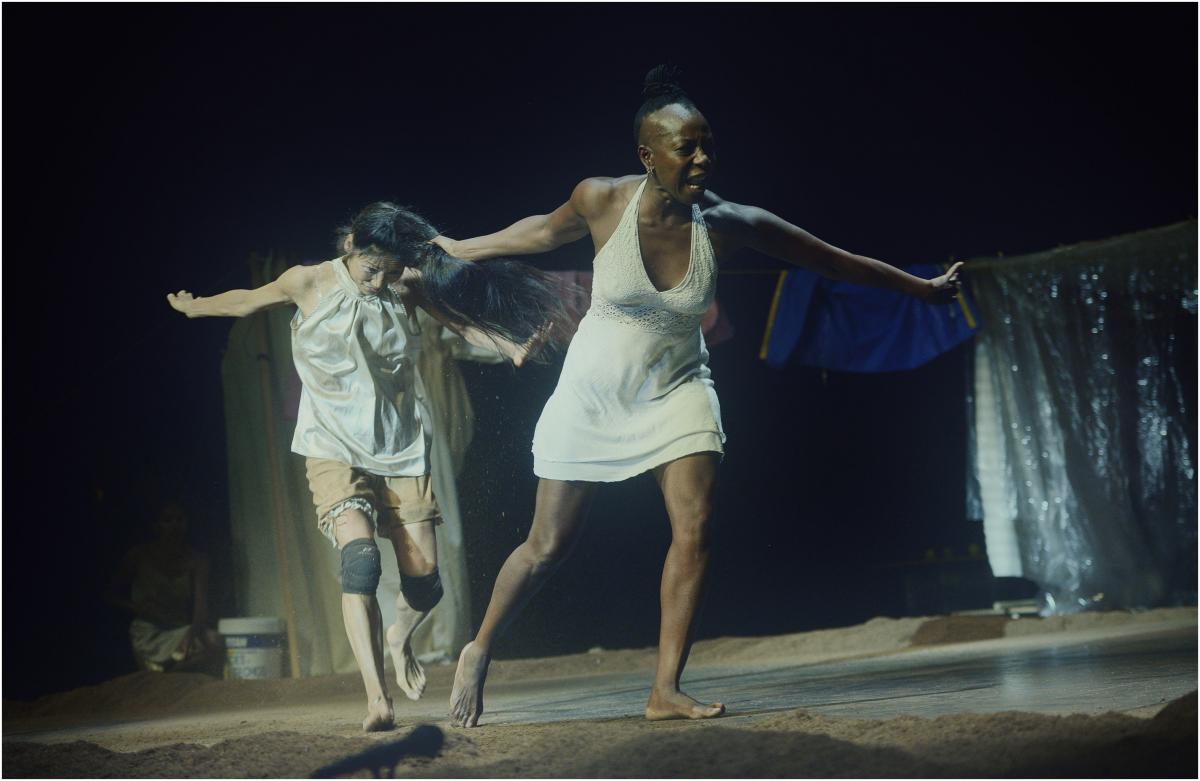

There is the muscular Julie who at a certain point mistreats the exile… “Minakò”, she screams all the time. Then Julie repents, asking to forgive her, she lifts her from the ground, holds her in her arms, and apologizes again. Then she ties her hair to a clothesline, and leaves her there, hanging like a puppet, moving like a puppet. Minako then starts to talk like a woman without wills, in fact, all fake smiles, and it’s probably what happens all the time on TV, when you want to sell who knows what to who knows who. Maybe soil. But we are all there to believe a puppet.

Perhaps WeWomen is a show that leaves us a bit perplexed and disoriented, but at a certain point it strikes, acting with the power of images. It waits for the conveyed symbols to work inside every woman to make them understand, once and for all, that the first change for the “feminine condition” concerns women, precisely, and not men. Men will not help the preconditions, but if the woman first considers herself as a creature given to sex, motherhood and domestic care, and if she first attacks those women who try to get out of their stereotypes that cage them, please, then don’t complain of male chauvinism. The most serious male chauvinism is that of women.

As long as women do not understand that they are their first and true enemy, there will be no feminism that will keep us from getting rid of anything. As long as there are women who first despise their freedom, acting as mirrors of male desires, there will be no revolution of the “feminine condition”. Instead, it’s nice to see Sol dancing with her black trousers over red tips, beating them like castanets on the floor, a little woman, a bit of a man, a bit like it comes naturally. The same Red Shoes from the Andersen fable, the ones that force the girl to dance until death, because she can’t manage her shoes, she can’t command her feet, which are the symbol of her freedom, leading her to the excess that takes her away from her true soul.

If we stop to look at it for a moment, we note that the people who support practices contrary to women’s freedom are often women. Women who judge other women because they are not enough women according to the generalized but not necessarily correct canons – women who infibulate other women, women who torture other women in the name of Jihad. They are also women who, with their gone mad feet, come back to their executioners. Slave women who throw the first stone against their own kind who are just trying to be free.