Don’t you feel, sometimes, to live in a completely different reality if you confront it with the world you see portrayed on TV, surfing the internet, flipping through newspapers…?

It’s like if there were, on the one hand, the world described by media, full of fear, made up of crises, catastrophes and terrorism, and on the other hand, your own world you directly experience every day, made up of people at least decent. No corrupt men or violent immigrants on the horizon. No rapists. No bombs.

But, despite this discrepancy, it is automatic: we all find ourselves here thinking that “this world sucks”, “it will end badly” and recently even that “it’s okay to limit our freedom a little bit in the name of security“. Without thinking that you are not only leaving behind your freedom, but you are also increasing violence and discrimination. What security requires.

The fact is that what media say is scary. By force: scrolling the homepage of a random newspaper on any day, in an average of about 30 news out of 40, we talk about:

- Abductions

- Explosions

- Wounded

- Attacks

- Victims

- Nuclear experiments

- Massacres

- Deaths

- Missing people

- Earthquakes …

Anxiety and fear only subsides when you come to news about fines or walls staining. Only sport is neutral (and it is not even sure) and Pope Francis (by now) is the only positive one.

How can we be optimistic?

First of all, not forgetting that media, for their “constitution”, will never help us to think positively because, since they have understood it, they only respond more and more to the logic of “sensation”: what sells is disturbance, deviation, violence …

Why? According to Steven Kotler, our survival is at stake. Writer and journalist from Chicago, Kotler is the author, along with Peter Diamandis, of one of the bestsellers published by the New York Times. It’s called Abundance: the future is better than you think.

Starting from a basic consideration: a huge amount of information has been hammering us for years on a daily basis, making orientation more complicated – once it was easier to choose between two things, rather than a thousand – but for survival instinct we have to come out alive somehow. How? Through our only tool, as well as our only filter, our brain.

Kotler argues that “to manage this overload, our brain makes a continuous selection effort, in an attempt to separate the essential from the superfluous. And since nothing is more essential to our brain than survival, the first filter that most of this information meets is the Amygdala. ”

And since Amygdala is the danger receptor par excellence and media communication is based on fear – “the blood sells” – the mix between the two is lethal: “anxious under normal circumstances, if stimulated Amygdala becomes hypersensitive : its answer is so powerful that once activated, it is difficult to switch it off and this is a real problem in the modern world”. It is somehow like a short circuit triggered between our brain and what we repeatedly see (things and facts that, thanks to globalization, more and more often do not coincide with what we live directly).

And evolution is also involved: among a tiger that lies in wait and a terrorist who could attack or an economy that could implode, there is a huge difference. “Many of today’s dangers are generic and potential, but Amygdala cannot perceive the difference“, Kotler writes, “or even worse: the system is designed to stay alert until the threat ceases altogether, but the potential dangers, by their very nature, never completely disappear. Add media that frightens us constantly with the aim of gaining market share to this and what we get is a mind convinced of living in a perennial state of siege”.

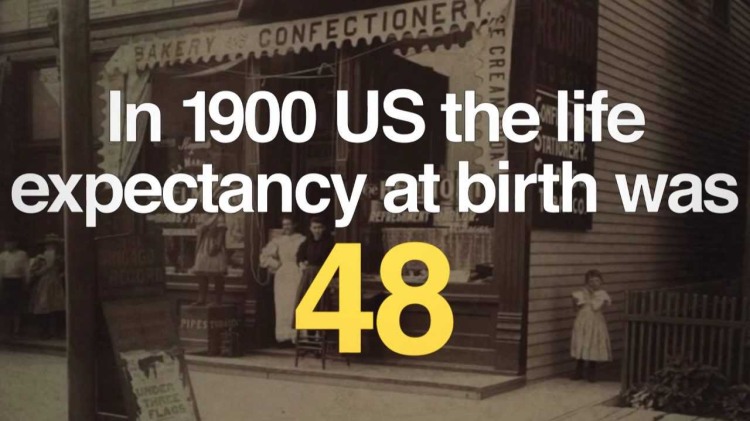

But then, which is the reality? “Much better than what most of us can suspect”. Kotler tries to make us look beyond world and media, perhaps putting them together, to see the bigger scenario. He can only rely on data, but, in fact, if you look at humanity throughout its history “no one ever stresses enough that”, for example, “violence is at historic lows and personal freedom at its highest. Over the last century, infant mortality has decreased by 90%, childbirth by 99% and average life expectancy has increased by 100%. The food is cheaper and more abundant than ever. Poverty has decreased more in the last 50 years than in the previous 500. Moreover, many of those living below the poverty line still have access to services that a century and a half ago the richest Europeans would not even dream of. And these changes are not limited to the ‘developed’ world. Today, in Africa, a Masai warrior with a cell phone can tap into vast archives of books, movies, games and music. Only 20 years ago, all the goods and services offered by mobile phones would have cost over a million dollars“. You hardly think about all this, but in the end anyone who has lived in this world or studied History at school can easily realize it.

According to Kotler what is happening is not accidental: at least once in a while we should consider that we live in a historical period in which “four explosive forces of change” – technological progress, DIY innovation, technofilantropia and “the billion of the lasts” – “have merged together and they are now able to promise that optimism that many do not let us see”. Not only “life”, also “history is now”…

[see you next week for the second part, where we are going to develop all the good news that they don’t tell us…]